Register here for the U-CARE Workshop. The form will open in a new tab.

Register Now

The basic idea of a superblock is to connect a grid of 9 to 12 city blocks with walking, biking, and expanded green spaces, leaving cars at the perimeter. This urban planning concept pioneered in Barcelona (ES) is a trend in many cities, and Berlin is one of them through the KiezBlocks initiative promoted by Changing Cities e.V.

Berlin’s urban landscape has Kieze (neighborhoods in Berlinerisch) comparable in size to a Superblock demanding comprehensive retrofits. Despite our Kieze being public and lively, street-level surfaces are sealed, trapping dangerous urban heat, rainwater is not used and lost, the greenery is weak for biodiversity, and walkability for vulnerable groups to priority locations is in question. In Berlin, what resembles a Superblock concept is heavy traffic lanes framing our Kieze but, most importantly, cohesive communities determined to lead transformational change.

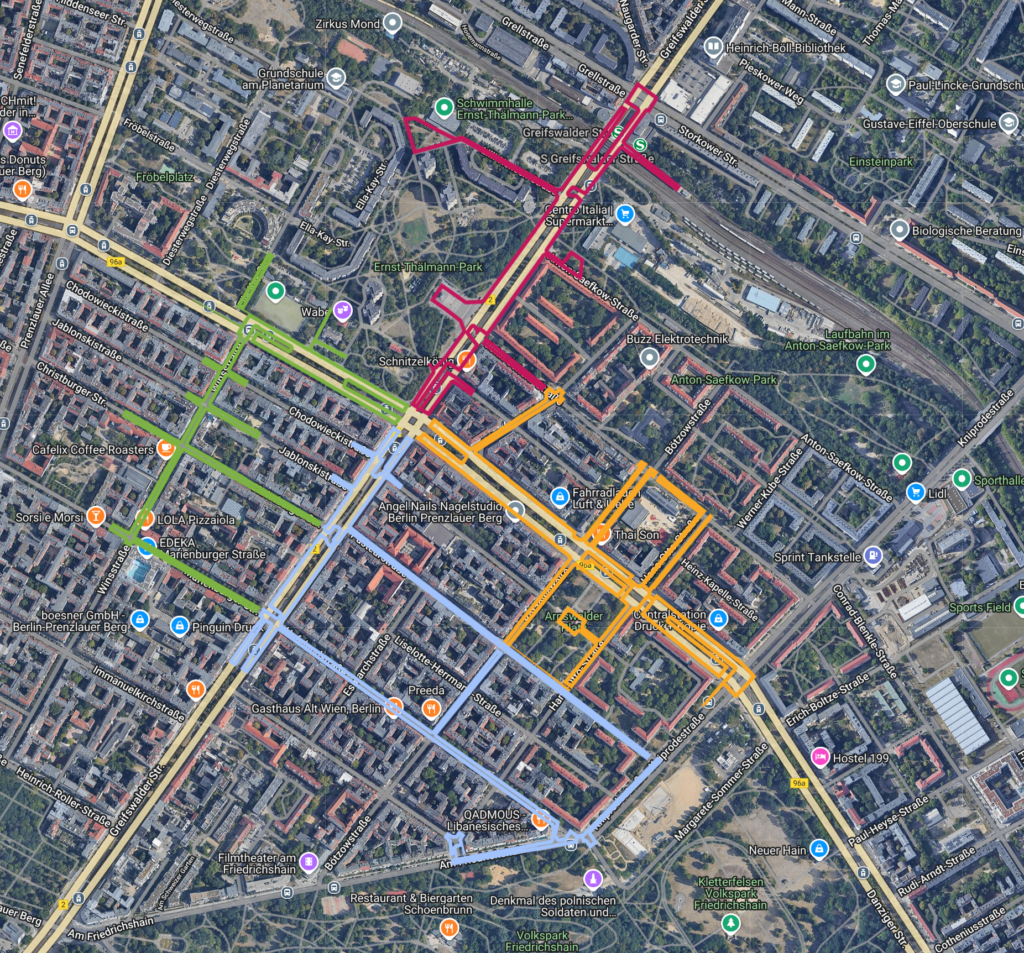

The Berlin case study focuses on four residential neighborhoods in the Pankow district: Bötzowviertel, Grüne Stadt, Ernst Thälmann Park, and Winsviertel. These neighborhoods are separated by the heavily trafficked corridors of Greifswalder Straße (M4) and Danziger Straße (M10), where car lanes, long street blocks, and limited pedestrian crossings create barriers to walkability and reduce access to public transport and green spaces such as Volkspark Friedrichshain.

Superblocks in Barcelona are entering a new phase in planning, their connectivity through green corridors to enhance liveability while making traffic adapt to its configuration.

In Berlin, the most recent draft of the Senate’s Mobility Act supports creating the Pedestrian Planner role for each of its 12 districts. The setting is favorable for retrofitting street environments within neighborhood limits and connecting to closeby ones, as Barcelona aims to do.

The project develops three different thematic pedestrian loops connecting the four neighborhoods and an additional fourth towards the intercity train station. All four loops facilitate environmental research and practical planning and design tasks.

Using the UrbanCare research framework, field studies were conducted as a first step aiming to co-organizing transdisciplinary problem-solving workshops with key stakeholders.

In the Berlin case, transit stops, crossings, and service entrances present barriers for slower-paced groups. Steep curbs, long crossings, and disconnected paths visibly hinder access, forcing detours or avoidance. These conditions contribute to unsafe mobility and reinforce health and access inequities.

visible water accumulation. Puddles form at tram entry points, and sidewalks become flooded, making it difficult for pedestrians to approach the platform. Wheelchair users are seen navigating around large pools of water or waiting for assistance, while individuals with visual impairments risk slipping on wet surfaces. These recurring disruptions highlight the vulnerability of certain groups in poorly drained environments.

Similar conditions are observed at street crossings, where low points in the pavement collect rainwater due to inadequate maintenance or design. Flooded intersections become obstacles rather than passageways, and individuals using walking aids are often seen retreating or seeking alternate, less safe routes. The pooling of water not only impairs mobility but visibly increases the risk of injury.

Near seating areas, depressions in the pavement allow stormwater to gather, sometimes making benches unusable. Slippery surfaces, often marked by algae growth, present a clear hazard, particularly for those with limited balance or reduced mobility. During and after rain events, these areas remain largely empty, signaling their inaccessibility.

Around building entrances, water is frequently seen channeled toward ramps and thresholds, pooling in front of access points. Wheelchair users and people pushing strollers are forced to stop, maneuver awkwardly, or avoid the entrance altogether. In each instance, rainfall visibly amplifies the spatial barriers already experienced by vulnerable populations, turning routine movement through the city into a hazardous task.

Rainfall consistently leads to water pooling at tram stops, crossings, seating areas, and entrances. Puddles block access, ramps flood, and algae-covered surfaces become slippery. Wheelchair users, those with walking aids, and others with limited mobility are often seen rerouting or hesitating, underscoring how poor drainage intensifies spatial barriers for vulnerable groups.

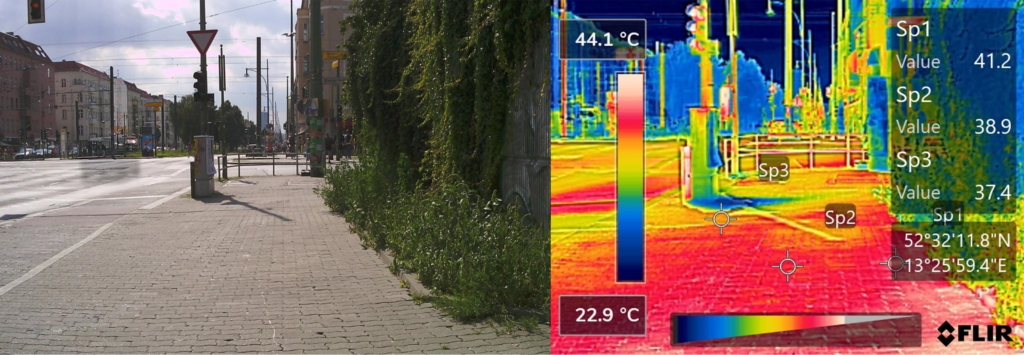

asphalt and concrete, and there is a noticeable absence of shading. During summer peaks, these surfaces radiate intense heat, and temperature readings in waiting areas often exceed 50°C. Passengers are seen standing in direct sun with no protection, visibly uncomfortable—some seeking minimal shelter behind signposts or leaning against shaded walls when available. Individuals with heat sensitivity or cardiovascular conditions appear particularly at risk.

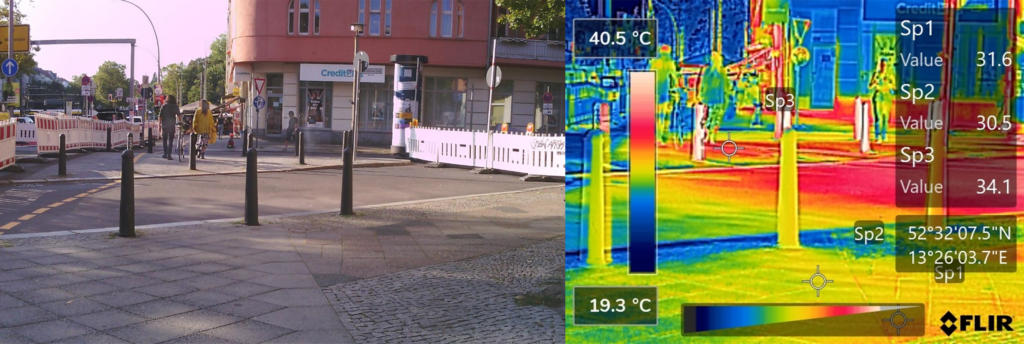

At nearby crossings, wide expanses of asphalt and stone paving stretch without interruption, and the lack of vegetation or overhead cover exposes pedestrians to full solar radiation. During heatwaves, people are observed rushing across the street, shielding their faces or pausing midway in rare slivers of shade. For slower-paced groups, the heat and distance clearly increase physical strain and risk.

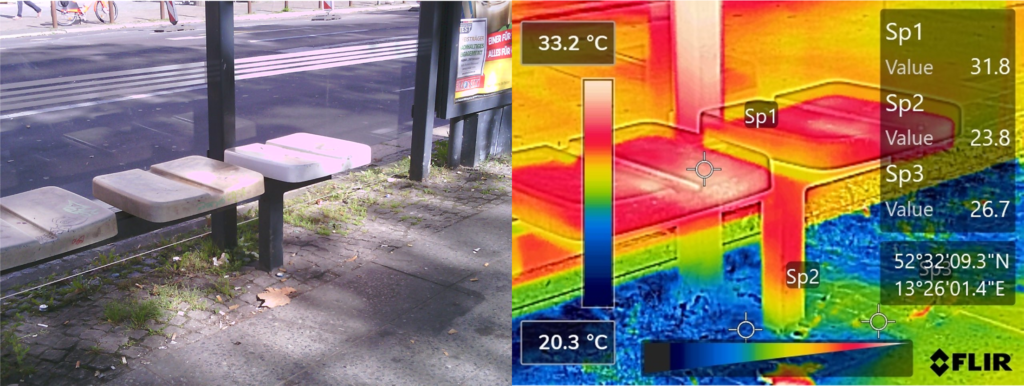

Resting points are often placed in fully exposed areas, surrounded by heat-absorbing surfaces. Without trees, pergolas, or cooling features, benches go largely unused during the hottest hours. The surfaces themselves become too hot to touch, discouraging use entirely and leaving vulnerable individuals without a safe place to pause.

Entrances to buildings—especially those serving medical or social functions—are frequently approached via exposed ramps or paved plazas. These areas trap heat, forming noticeable hotspots. During peak temperatures, individuals arriving for appointments or caregiving duties are seen pausing at the edge, visibly affected by the heat before entering.

Extensive asphalt and a lack of shade create intense heat around stops, Crossings, resting areas, and entrances. Surface temperatures often exceed 50°C, leaving passengers exposed and visibly distressed. Benches remain unused, crossings become physically demanding, and entrances turn into heat traps—posing clear risks for slower-paced and heat-sensitive individuals.

almost entirely sealed with concrete or asphalt, offering no signs of vegetation or permeable surfaces. The environment appears dry, hard, and sterile, with no natural shading, cooling, or filtration—creating a visibly uncomfortable atmosphere, especially during warm weather. These fully mineralized zones show no ecological integration, contributing to a fragmented urban landscape where green corridors are absent and habitat continuity is visibly disrupted.

At crossings, one observes long stretches of uninterrupted paving, with no planted strips or green buffers to soften the space or provide ecological value. Despite ample space along the edges or medians, opportunities to introduce low-maintenance vegetation are overlooked, reinforcing both environmental degradation and a sense of psychological harshness.

Respite areas typically feature ornamental gravel, compacted earth, or decorative planters with minimal biodiversity. Bees, butterflies, or shade-loving plants are notably absent. These spaces, though intended for rest, offer little in terms of comfort or ecological function—remaining empty or underused, especially during hotter hours.

Around building entrances, sealed surfaces dominate, with no visible integration of greenery or biophilic elements. Rainwater has nowhere to go, and heat radiates off the pavement, creating a harsh threshold to public services. Users arriving for medical appointments or community services are left without the calming presence of nature. These missed chances to introduce vegetation not only heighten environmental stress but also remove the potential for restorative, health-supportive urban experiences.

Surfaces are almost entirely sealed, with little vegetation or permeability. The resulting environment feels dry, harsh, and ecologically barren. Crossings, resting areas, and entrances lack green buffers or biophilic features, offering no cooling, comfort, or habitat value. These missed opportunities leave public spaces fragmented and unwelcoming, especially for those seeking relief, rest, or recovery.

6.4 Km of field research

Data Analysis Reports

Collaborating partners

Alvaro Valera Sosa, Jacob van Rijs (2025)

Technische Universität Berlin

Jacob van Rijs: Project Coordination, Supervision

[email protected]

Philip Stilke: Deputy Coordination

[email protected]

Krati Agarwal: Data Analysis Assistance

[email protected]

BHL Building Health Lab

Alvaro Valera Sosa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Environmental Health Analyses

[email protected]

BHL Building Health Lab

We battle climate change impacts on urban ecosystems and health across different European climate zones.

Co-funded by the European Union.

We support city makers in implementing sustainable development goals with evidence.